I have this recurring nightmare where I have to perform a car jump over a collapsed bridge like I’m in a road trip movie. Every time, without fail, my car plunges into the water. I always manage to narrowly escape, backpack in tow. I carry this backpack almost everywhere I go. This usually incites a strange reaction, to which I respond by comparing myself to Dora the Explorer in a self-deprecating tone, even though Hannah Gadsby tells us self-deprecation is not humility–it’s humiliation. I also know we’re not supposed to tell people about our dreams, but I am a work in progress.

Public speaking has always felt akin to this recurring nightmare–repeating itself again and again over time. Counting the paragraphs to determine when it would be my turn during popcorn reading. Making sure not to say “like” during my final senior portfolio presentation, but feeling the heat of my face take the spotlight. It has carried into adulthood and can take many shapes. My body’s response doesn’t waver whether I’m in the company of one or one hundred. For many, mindfulness techniques and belly breathing can be a balm, but to me, it’s a blow. Another reminder that something in me is different.

Autistic people often have higher levels of cortisol–the “stress hormone.” Many of us go through life teetering on the edge of burnout because of things like overstimulation, communication differences, and being misunderstood.

Public speaking can suppress and weaken an individual’s immune system because the stress associated with it increases cortisol. One of the benefits of being self-employed is that my Google Calendar is cushioned with downtime following any sort of public speaking–whether it’s a presentation, podcast interview, or potential client call. I am often catapulted into chronic illness from oversocialization, despite a daily dose of beta blockers.

Over winter break, I recently triggered TMJ because I was unknowingly clenching my teeth during a playground-themed escape room. We escaped with two seconds to spare and apparently the suspense was too much for me. The flare-up lasted for weeks and was eased by soft foods, anti-inflammatories, and hot and cold compresses. In summary, I am the kind of anxious person who gets activated by the wholesome fun of an all-ages escape room. Despite all of this, I brace myself for impact and still say yes to things outside my comfort zone.

Most recently, I was invited by the Abington Township Public Library to participate as a book in their Human Library event. The Human Library, or “Menneskebiblioteket” in Danish, was created in Copenhagen in 2000 and is now available in more than 80 countries. The organization attempts to foster conversation and build community by asking folks to “unjudge someone.” Participants, or readers, can “check out” human books to have a discussion about their life experience. The human books are often a part of a group that is subject to prejudice or stigmatization.

The library organized over a dozen people to serve as human books, including a Vietnam War veteran, Disabled individuals, a child of incarcerated parents, trans and queer people, immigrants, and others.

It took an emergency craniotomy months before the COVID-19 pandemic to launch me into Disability justice work—providing me with the language I needed to fully realize my queerness and transness in my mid 30s. Autism and ADHD diagnoses came soon after (with OCD loading next on the queue).

Once all of these identities clicked, I felt the need to be visible with my vulnerability in hopes that others would see themselves and realize that they, too, are not broken. I wasn’t sure which of these identities the library would want me to speak about. My expectation sensitivity was building as I scripted possible scenarios in my mind. I was premanufacturing potential comebacks to strangers who might misgender me or tell me Autism is linked to vaccines. It *didn’t feel dissimilar to when I arrived at my Autism assessment, armed with “proof” that I was Autistic enough–only for my Autistic evaluator to tell me that I had a “perfect Autistic accent” within minutes.

* I’m intentionally using a double-negative because my PDA (or pervasive drive for autonomy) encourages me to disrupt the powers who tell us what makes a positive editorial experience and what makes a “rustic, uneducated” one.

I arrived at the library early and sat in the parking lot taking deep breaths, even though they are rarely effective for me. I recorded a video saying, This is me before I go into the Human Library Project, fully prepared to make a follow-up after, flush-faced and crying. Like those TikToks you see of aloof boyfriends before going to see Wicked, followed by an immediate tearful reaction at the end of the film, which will now undoubtedly become their entire personality (also, same).

I noticed a patron in the truck across from me and in an effort to not be perceived, shook off my nerves and went inside. I was handed a sheet with pre-chosen titles of the human books and asked to review mine.

“Non-binary person with Autism.” Looks good! Moments later, I reconsidered my people-pleasing response by asking to review it again to make a minor edit. “Autistic non-binary person.” Not winning any Pulitzers with my title, but points for clear, accessible language. I prepared a response to defend my revision in my head. You wouldn’t say person with gay, would you? But it was unnecessary, because I was met with a welcome smile.

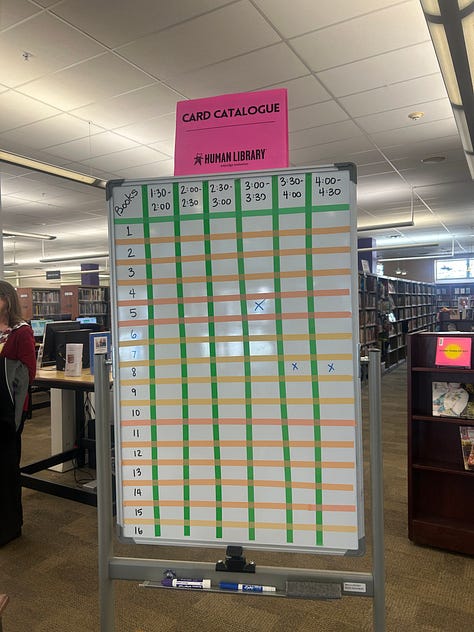

A card catalogue was on display at the front of the library in the form of a large whiteboard sectioned off into a chart with green and orange masking tape. Sixteen human books were given half-hour time slots with individual readers, spanning from 1:30-4:30pm. I was asked about my capacity and when I would like to schedule a break. I responded by saying that I didn’t need any breaks, but agreed to refuel at some point in their staff room, which was stocked with snacks and further solitude.

I was directed to my section–a trio of green chairs in the New Books department . I took a photo of an Escape Room game on the way to ask my partner if I should check it out for us. It was then that I was reminded my doctor told me to avoid excessive conversations due to my TMJ flare-up. I wondered if she would consider a three hour conversation with strangers to be excessive.

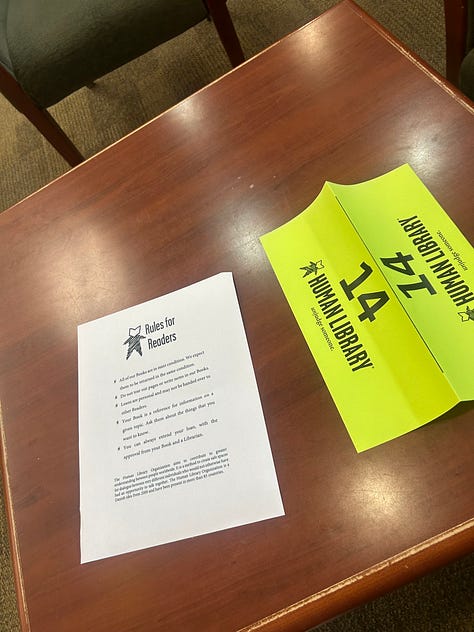

Nonetheless, I sat in the cushioned, olive chair and traced letters in the velvety fabric, prepared to spend the afternoon unapproached. A fluorescent yellow paper sat folded at the coffee table in front of me, alerting patrons that I was #14. I would soon come to realize that book #13 was a no-show. Later, I engaged in a one-sided “bit” with readers who were looking for book #13. I would alert them that #13 wasn’t able to make it, but that they could instead end up with my disappointing company. Yes, self-deprecation is bad, and Janeane Garofalo had her self-loathing roots in me long before I knew about the charms of Hannah Gadsby.

Someone with glasses tucked in their hair approached me, calling me Joe and saying it was nice to see me. My name isn’t Joe. “Oh,” they said. I get that a lot. They walked away while quietly apologizing. I spent several minutes reevaluating my strange response as patrons browsed the new books behind me.

A person in a camouflage sherpa vest approached my library nook. I had previously waved and said hello to them as they walked by, as I do with nearly everyone. “You seemed nice,” they said, announcing themself as my first reader. They, too, had glasses resting in their hair. I drew my eyes toward their statement necklace as I spoke, reminding myself I didn’t have to mask by making eye contact. Their husband was waiting patiently in the library while they scheduled slots with human books, which I said was sweet. We spoke about how they never wanted to have kids because of sensory issues. How they had a friend who raised goats on a farm and how tiring that seemed. That they didn’t personally know anyone Autistic, apart from a child and some non-speaking patrons at the library where they were employed. I talked about some of the accommodations that make my life more accessible, gesturing to my wireless Beats. I shared that I wear them when I have to run errands at places like Target to make being in the world easier. “I just don’t go to Target,” they said, laughing. We talked about my 21-year-old pet chinchilla, Maude, who they thought would make a cute coin purse if she ever died.

At one point, a person in their 80s walked by. They were wearing a purple sweater, purple coat, purple purse, and beret. I gasped when I saw their Elphaba-style eyewear and told them I loved their glasses. “Me too,” they said, while shifting their weight with their cane and glancing around. I love seeing people accept compliments so well, I told my new reader friend. That’s something I find challenging. “Well, you’re cute, so there!” they said, playfully. “I guess you really can’t judge a book by its cover,” they said, wrapping up our session together. I made so many assumptions of how they might judge me based on their appearance and biases, when I should have examined my own (ageism, for one).

My next reader was a 16-year-old tuba player with a red pleather jacket and dangling dinosaur earrings. We exchanged nervous energy, unsure of what to ask each other. Soon, another reader in a cheetah windbreaker joined us and took a seat. The new reader immediately shared how they thought their child might be Autistic. And that their mom may have been as well. They called their friend over–the person dressed in purple. I exclaimed how I had complimented their Elphaba glasses and that I’d love for them to join. We pulled a chair over from #13’s section and I asked how the pair knew each other. I was surprised that I felt a release in pressure as our group grew larger. They shared how they met via political organizing locally, calling themselves “messy” throughout the conversation. The teenager spoke about their love for marching band because it allows them to move around with music. They recounted how they often sprint outside to their favorite songs and their neighbor asks if they are training for a marathon. They say no, but we encouraged them to lie and say yes to be left alone. We shared the definition of stimming–or self-stimulatory behavior–and the different ways we all stim. We talked about glasses and the affordability of Warby Parker. The 16-year-old said that their parents pay for glasses, which made the rest of us feel old in a wholesome sort of way.

The person in the cheetah windbreaker spoke of one of their book club’s recent picks: Yellowface and the theme of cultural appropriation. And James, the reimagining of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from a Black author. How it felt being the only Black woman in the book club and having all of the white people stare at them when the n-word was used. The interesting choices the Autistic author made when writing about Huck. We talked about the ways in which Autism is stigmatized and I compared it to left-handedness. The reader in the cheetah windbreaker shared how they were forced into right-handedness in school in New York.

I discussed my career as a self-employed photographer and how wedding days can be filled with a lot of complicated feelings and grief. The person in the Elphaba glasses shared how their father wasn’t at their wedding because he had died. Their friend corrected them by saying that he was at their wedding. “Remember? He was at your daughter’s birth.” “Oh yeah, sometimes I get confused,” they responded, apologizing for their memory and sharing that they have dementia. They visited a friend in a memory room just yesterday. I had never heard of such a space until that week when I started watching “A Man on the Inside” with Ted Danson.

We talked about Autism diagnoses and the lack of access for adults, especially the more marginalized you are in the community. There were echoes of “that’s such bullshit” within the New Books section, while patrons swished by in their winter gear. The two reader friends warned that when you’re older, you are invisible to people. How they had just spoken to a human book and wheelchair user who felt the same. They responded to my knowing glance by saying they don’t let that discourage them. “That’s when we can sneak in and get shit done,” they said. A volunteer let us know our half hour was up.

I exchanged hugs with the two friends and welcomed a trio of new readers. A reader with a white KN95 approached, so I slipped my mask back on. We skipped the small talk and delved into light topics like sibling estrangement. A volunteer with the Abington Township Human Relations Commission asked how I define words like “queer” or “trans” for myself. A half hour passed with rapid speed and I was reminded to check out the break room. Green grapes burst in my mouth as I exchanged title names with other books, while trying to respect their social capacity.

For my next half hour session, two fellow books sat on either side of me, introducing themselves and letting me know others had recommended they stop by. One was a parent of Disabled children. The other was a trans individual, who I insufferably called “a youth.” We were soon handed kraft gift boxes from the Library Director, who thanked us for our time. We spoke with the Director about the success and busyness of the event, which was perhaps in part due to the Eagles game not starting until later that day. The Director asked us about our experiences as books so far. We agreed that we were, for the most part, pleasantly surprised by the respect given to us by readers.

A social worker from New Jersey soon joined us, while the trans book headed back to greet their own readers. The parent shared how their 29-year-old was questioning their queerness and self-diagnosing as Autistic, which resonated in many ways. We spoke about why I use the word “queer” as part of my identity and how for some, that word might not feel like a good fit. We unpacked the differences between identity-first and person-first language when talking about Disability and Autism. The social worker shared that they were taught to use person-first language in academics. I explained that it is up to the individual to let us know what words they’d like to use for themselves. We discussed how certain words have been reclaimed by marginalized communities over time. And how it feels to hear slurs that are still used today.

At my most recent dental cleaning, the hygienist used the r-word when speaking to a coworker during my routine x-rays. My mouth was wide open and my eyes grew with it, unable to process how to respond. We talked about the traumatization of the medical-industrial complex while catching the glance of a person waiting in the neighboring section. I informed them that #13 wasn’t present, but that they could join us if they wanted. They sat alongside us for a bit while we wrapped up to prepare for the final conversations at 4pm.

I checked my phone for texts and saw my partner gave me an enthusiastic thumbs up reaction when asked about the Escape Room game. I made a mental note to grab it before the library’s closing, along with the children’s books I added into a Google Doc. A fellow bespectacled person in a black coat and casual button-up meandered into my quiet corner. They told me they had driven in from Lancaster and chronicled their experiences as a third-born child with five brothers, one sister, and a schizophrenic mother. They had an ease to their inquisitive nature. “How was it growing up?” I liked the openness of their questions. I tried to share the positives, like how I enjoyed creating worlds for myself alone in my bedroom. My experiences masking as a class clown. “Did that help you?” I explained that it felt similar to how so many traumatized children coped by turning into comedians, like Jim Carrey. That I’ve always tried to heal my pain through humor. I immediately apologized for sounding conceited enough to compare myself to Jim Carrey. In a moment of unexpected vulnerability, they started listing the ages of their children, of which there were more than a handful. In the middle of the list, they shared how one of their children had died in 2020. They took a breath, seemingly processing after saying the words aloud. I can’t even imagine. I know there’s nothing I can say to make it better, but I’m sorry. You’re doing a great job. “Do you think in pictures?” they asked. I repeated the question outloud to give myself time to answer factually. Do I think in pictures? My lack of a response prompted them to explain further. They shared how their Disabled son also has ADHD. How my mannerisms and the way I tangentially approach conversations remind them of him. How they are constantly taken aback by his intense intuition. How they’ll arrive from a hard day at work and walk ten feet from their car to the inside of their home, only to be greeted by their son, who reads their face and asks what’s wrong? I responded by sharing how many neurodivergent folks have strong pattern recognition and typically pick up on social cues efficiently, despite what society may think. That many inventors and creators are Autistic, but perhaps never realized that about themselves. How it’s a gift for his son to have an ADHD diagnosis, so he doesn’t have to reexamine his entire life as a late-diagnosed adult. And how we sometimes talk about Autistics as having a strong sense of social justice, but like everything, there's duality. Elon Musk thinks he’s being socially just, and yet, here we are. Do you think it would be rude for me to open this now? I rattled the brown, unmarked gift box in my hands. I removed a white mug and placed it between my palms while dismissing the way society enacts etiquette. An italicized, maroon serif font read “life is better with books.” I was excited to add it to my collection.

They shared how their son was an old soul. I used to be told the same thing, and now as a 40-year-old, people infantilize me by calling me a rockstar or superhero. It’s like once you’re an Autistic adult, the way people perceive you swaps. After recalling they traveled from Lancaster, I shared how I grew up not too far away in Central Pennsylvania. That I felt shame for my family’s values not being aligned with my own.

You’re seemingly progressive for someone from Lancaster. That’s impressive. “What do you mean by progressive?” I fumbled over my words while explaining that I felt comfortable opening up about my transness. That I was recently surprised by Lancaster’s robust queer scene. I quickly changed the topic by asking for confirmation that whoopie pies originated in Lancaster–a fact I already knew. I almost shared how I went to college in Kutztown, where Mennonite farms dotted the countryside. I revised my thoughts and mentioned that we made our own whoopie pies for our backyard wedding.

We discussed the importance of destigmatizing therapy and what it’s been like as an Autistic person experiencing cognitive behavioral therapy (or CBT). In the past, therapists have asked me where I feel my emotions, but I use logic to rationalize things. Most people *feel* emotions in their body, that is why they’re called feelings, I infodumped. During my Autism assessment, my evaluator shared a graphic that visualized the ways most people experience emotions in their body. Many Autistics have alexithymia, which makes it difficult to identify, understand, and express emotions. In the visual, there’s a photo of a perfect pile of gummy bears (Allistics) contrasted with a bag of melted gummy bears (Autistics). Our hyperconnected brains make everything more intense, resulting in cues that can become an unidentifiable bag of mush.

An announcement over the loudspeaker alerted patrons that the library would soon be closing. I stretched my jaw widely, feeling the stiffness from speaking setting in. Thank you for chatting with me. I have to find some Wolverine comics for my 6-year-old before they kick us out. A person in black glasses with a long, blueish grey dress and tan cardigan greeted us while smiling. The reader introduced the person as their wife, who was also participating as a book. When asked what book title I was, I shared, echoing the question back to them. They explained how they were there to represent the Mennonite community. The reader asked their wife to show me a photo of their family, while explaining how much I reminded them of their son who has ADHD. I was soon handed a pastel marbled case with a glowing family photo of everyone smiling in modern, monochromatic hues. My heart sank knowing there was a child missing from the photo. As the reader’s wife turned to tuck the phone away, I noticed their white hair covering. Thus began the rumination of our previous conversation. You’re seemingly progressive for someone from Lancaster.

All of the previous stereotypes my mind held about Mennonites began to unravel. I thought about the readers who met me with, “But you don’t look Autistic,” and how I was no better. How jaded I was for thinking I’d be the only one on the receiving end of preconceived notions. How I assumed I’d experience the brunt of people’s biases while having to reeducate them. I was instead reminded that I have my own biases that will need to be reexamined in perpetuity.

The more I connect face-to-face with people–real people, not bots or trolls–the less opening up feels like a recurring nightmare. And the more faith I have in humanity, despite being in an era of book bans.

Two days after the event, I bounced on my walking pad, basking in the cool glow of my Gmail inbox, mouth agape at a new form submission. A trans, neurodivergent couple was inquiring about photography for their wedding at a queer-affirming venue in Germantown. A Mennonite church. It was the reminder I needed to give myself, and others, grace as we’re all (hopefully) unlearning.