Honestly, Must I Write You A Poem?

On the Cuteness, Buddy-ing, and Infantilization of Autistic People: Comments from Season 2 of Love on the Spectrum U.S.

[Content warning: This essay includes topics that center around ableism and mention transantagonism.]

As someone who has watched both seasons of the Australian and American versions of the reality television show Love on the Spectrum, it makes sense that my TikTok algorithm is filled with passionate takes from fellow Autistics. I don’t purport to have anything new to say that hasn’t been shared already, and yet here I am, eating canned dolmas from Trader Joe’s, while scraping together some content.

The show defines itself as a romantic docuseries, where “people on the autism spectrum look for love and navigate the changing world of dating and relationships.” My brain has a hard time not capitalizing Autism, so I wanted to make note that the show uses its lowercase counterpart. Many Autistics capitalize the word to indicate it is a part of our identities that we pride ourselves on, and to celebrate its rich history and culture, along with the community we all continue to build together (even when we’re battling each other on TikTok about tv shows).

When writing about disability, I opt to use identity-first language (saying “Autistic” or “Autistic person”) instead of person-first language (“person with Autism”), to reinforce the idea that disability is not a bad word. Devon Price writes in Unmasking Autism, “Disability service organizations that are not run by disabled people tend to advocate for person-first language.” But again, like all things, this is not monolithic.

When using language like “person with Autism,” it can sound a bit like “person with queerness,” as if a person could or would want to be separated from their Autism.

We are also not a disorder, so referring to us as a “person with ASD” (Autism Spectrum Disorder) can be offensive to many. While ASD is often a label assigned to us, it is deficit-based, pathologized, and promoted by ABA. The phrase “on the spectrum” suggests ASD, which is medical and can imply we may want to fix it or seek out treatment.

There isn’t a universally-preferred language in the community, so it’s best to use whatever language works for the individual. Though, outdated labels can further oppress the community by encouraging allistics to use them, which can be harmful.

We’re all learning together and language is constantly evolving. In order to keep this work accessible to everyone, we need to offer grace when we don’t all choose to communicate in the same way. When in doubt, we can always use direct language about what kind of support a person needs.

After 39 years on this planet, I’ve come to the natural conclusion that descriptors like “beautiful” or even “hot” may forever be out of reach for folks who look like me. Or for those of us who act like me–bopping around, flailing, and squealing at the delivery of a Bloomin’ Onion.

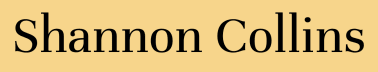

If there were a pie chart of physical affirmations I’ve been on the receiving end of, “cute” would be the largest slice by far. “Bud” or “buddy”—a pal-adjacent word that comes with the territory of being cute—would be next.

As a wedding photographer who often works alongside queer marriers, I try to be mindful of avoiding the word “cute” when hyping folks up (though if someone lists that as an affirming descriptor, I’m more than happy to oblige). Queer partners are often overly described as “cute,” which is one of the reasons I always ask folks what words feel good to them. For some, affirmations aren’t really their thing, and they’d rather not be verbally perceived at all in that way.

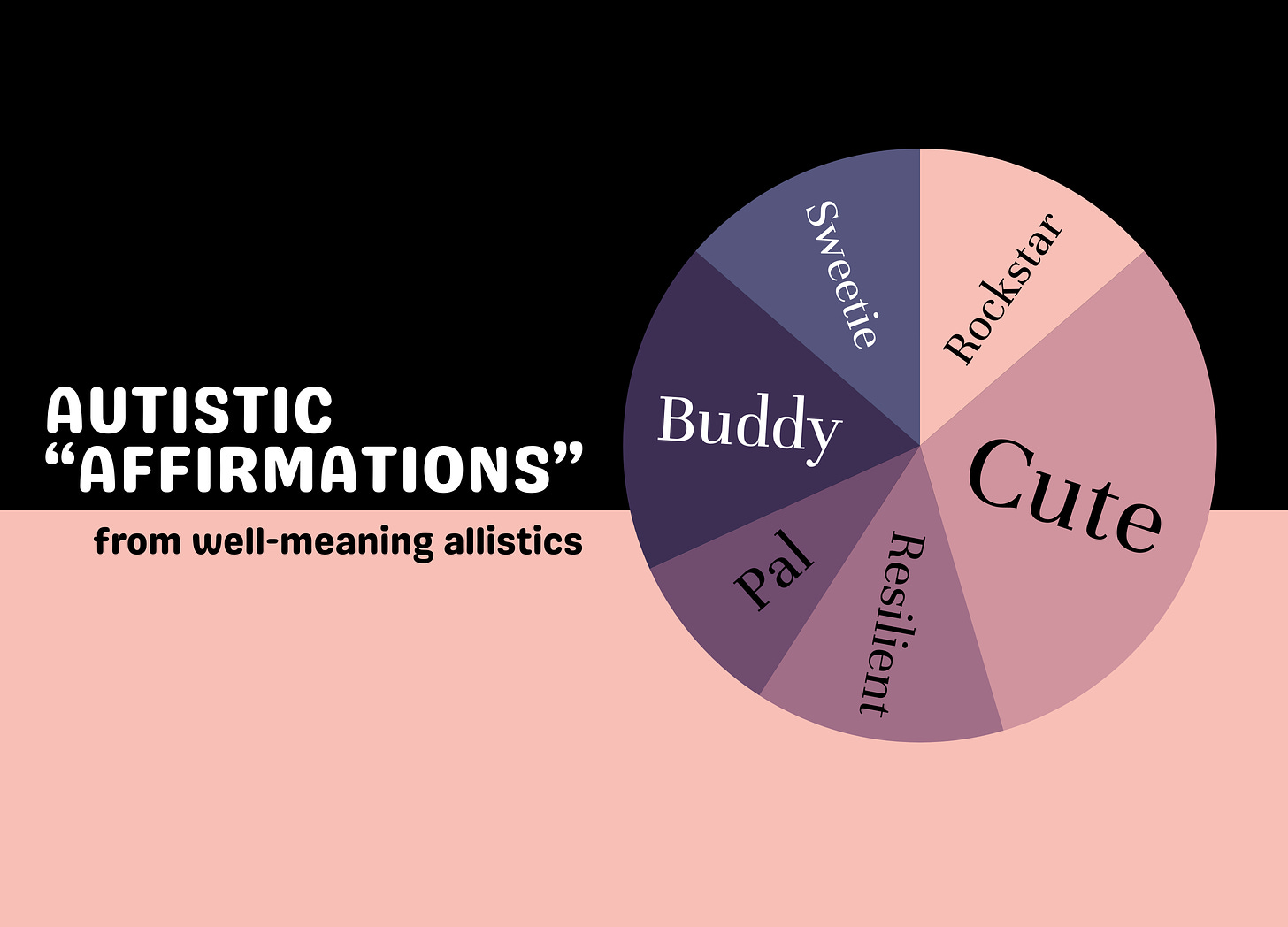

Beyond being potentially viewed as condescending or infantilizing, terms like “bud” or “cute” can be loaded when directed toward folks in the queer community. On a recent episode of The Tonight Show, Jimmy Fallon called actress Hunter Schafer “bud” twice. Trans actor Alanna Darby shared on TikTok about why calling a trans woman “bud” can be a microaggression.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

While some may consider “bud” gender neutral, many on X—formally known as Twitter—have shared that not only is “bud” masc-leaning, but it is degrading. Others have pointed out how Fallon has called cis women “bud” over the years and that Hunter has not acknowledged the discourse. Regardless, the statement still stands that some feel patronized when being called “bud,” while others seem fully unbothered.

If you search Love on the Spectrum on TikTok, there’s typically a pattern of the types of comments people leave. Take 25-year-old Connor, for instance. Hundreds of people have been declaring, “We have to protect him at all costs!” On a recent TikTok, Connor shared fun facts about capybaras, which resulted in a choir of “Hope you find love, Buddy” type responses.

There’s a pattern in the words commenters use when expressing that they’re feeling “hopeful” for him and some of the other Autistic cast members. Innocent. Cute. Baby angel. Brave. Precious. Pure. Adorable. A national treasure. A king. Sweetie. Forrest Gump. Golden retriever. Rockstar.

As an Autistic person, I’ve been called “resilient” or a “rockstar” for merely existing and it’s not the compliment allistic people think it is. Before we go too much deeper, it’s worth restating that the Autistic community is not a monolith. While these are my thoughts and opinions, there are certainly Autistic folks who would disagree and that is completely valid.

In episode 2 of the most recent season of the series, Connor seems dysregulated outside of the speed dating event and calls his mom for support. After an encouraging chat, he heads inside to sit back down and take a deep breath. Off camera, a woman asks, “You doing okay, buddy?”

In Episode 3, Tanner’s mom visits to help prepare him for his first date. During her entrance, she enthusiastically calls him buddy twice. The episode cuts to her explaining Tanner’s backstory in a confessional, during which her speaking tone shifts to being less sing-songy and more straight-forward.

This clip is highlighted in a TikTok where the caption reads, “Tanner is the real life Buddy the Elf. Most joyous person on Earth✨” Comments range from “Why is he so pure-hearted and precious!?” and “I NEED TANNER IN MY LIFE TO CURE MY DEPRESSION” to “I would die for this man.” This desire to protect and die for adult cast members subtly alludes that they need saving. Or, sometimes, the very opposite: “We need Tanner to save us all!” Someone else compares him to “a real life Olaf.”

There’s an echo of comments like, “I wish I could be this happy like wow he is really truly happy.” Another person asks, “Can he experience sadness?”

For many of us Autistic people, there’s often a projection of cartoonishness and infantilization that can be directed toward us. Or what some folks refer to as the Uncanny Valley Effect. Perhaps that’s because many of us have spent our lives trying to emulate what is expected of us. In my case, this studying of humans has led to a lifetime of watching reality television as a special interest.

In episode 2, Tanner’s introduction starts by him asking Director Cian O’Clery, “Hey, am I doing my eyebrows right?” In a later episode, Tanner shares with Autistic coach Jennifer Cook how he puts pressure on himself to perform by smiling and laughing. And that “even if I’m quiet sometimes, that doesn’t mean I’m in a bad mood, I just don’t have a lot of things to say.” Jennifer provides comfort by assuring Tanner that people will still like him, and that they’ll just think he’s being quiet.

Masking—or camouflaging parts of ourselves in order to better fit in with those around us—is something I did for my entire life without realizing it. It was not typically a conscious choice, and at the same time, it was exhausting to maintain. Potential examples of masking can be seen in the beginning of quick-cut confessionals from the cast, whose straight faces turn into smiles once production is ready.

As a late diagnosed, queer, Autistic person, I’ve found that well-meaning advice from folks telling us that people will still like us if we don’t smile isn’t always true. It becomes even more complicated when you’re perceived as a woman, as some men seemingly feel like it’s their duty to tell you to smile.

When our joy fades and our tone shifts, many friendships and relationships will come to a halt over time. For some of us, we will struggle to make sense of where we went wrong. We will smile more. Spiral about the what if’s. For others, we will drop the mask and determine that being alone just feels safer.

I spent six years as a volunteer crisis counselor for TrevorChat, The Trevor Project’s text and chat support service. During our volunteer training, we were instructed to avoid the famed phrase, “it gets better,” because for some queer youth in crisis, that was a promise we couldn’t keep.

For those of us who hold the privileges that allow us to unmask, it can be a telling process. Friends and family might miss the version of ourselves we never were. We might miss that version, too. For some of us, it won’t get better. People won’t still like us. We’ll make them uncomfortable. But if we overcorrect and smile too much, we’ll make them uncomfortable, too.

Journey, who is introduced in the fourth episode of Season 2, is no stranger to being called cute by viewers. As an 18-year-old Black woman who self-diagnosed the year prior, Journey expresses her love for baking and painting. After sharing oil pastel sea otter drawings, Journey explains her attraction to women and nervous anticipation for her first date. As an important aside, Nico Hall writes for Autostraddle on how the show “Fails to Give Its Queer Woman the Dates She Deserves.”

In episode 6, Journey gets ready in her Chicago home for her second date. Her sibling Stevie shares advice on flirting and body language. “When I was taught how to make conversation and do eye contact, it was like look at them for 3 seconds, then look away, then look at them for 3 seconds, then look away.” Journey’s siblings explain to not stare at her date for too long, because that might be perceived as creepy or scary.

Trying to figure out the formula for expressive, but not “weird” eyebrows, or an appropriate amount of eye contact can be daunting. I’ve only just recently given myself permission to allow my eyes to dart mid-conversation—which feels like the ultimate act of rebellion from someone whose risk-taking scores literally plummeted into the negative numbers for my Autism assessment.

And yet, the fact that others have been taught how to perform eye contact is almost comforting—a reminder that we are not alone in this confusion.

When Connor is being asked questions about a recent date, he responds with the same answer, growingly frustrated, asking his family, “Honestly, must I write you a poem?” There is a certain pressure that can build when we aren’t facilitating relationships in the way allistics, or non-Autistic people, might hope we can.

While Love on the Spectrum attempts to address longing and loneliness, it is sometimes through the presumably allistic gaze of the cast’s support people. “I see a very lonely man,” Connor’s (honestly incredible) mom tells her son, sharing how she wished Connor was surrounded by more than just family. “I blinked and he was 24,” she shared, on the heartbreak of Connor not having anyone else. She expresses how she just wants him to be happy. Connor’s brother responds by saying he thinks Connor is. The scene cuts to Connor stimming on their living room couch, with the sounds of car crashes blasting from the speakers, presumably as he watches a favorite action film.

The editing choice to include pet reactions while the Autistic participants are engaging in conversations feels like a wink to the camera, where I’m not sure if I’m in on the joke or if we’re the punchline. Connor’s shih tzu, Chewy, side-eyes the camera while Connor narrates what’s happening in one of his favorite movies, Transformers. I’m not one to typically complain about animals getting screen time, but there’s something off-putting about cutting to a dog perking up its ears in reaction to an Autistic cast member. I think for me, it’s the choice to edit it chronologically, when it’s very likely that things didn’t happen in that order.

In episode 4, Dani is singing with Jake at a piano during their date in a restaurant. The camera cuts to a seemingly disgruntled person in the crowd. Whether it’s a dog looking startled or a stone-faced restaurant-goer, these are instances when the neurotypical (and ahem, canine) gaze continue to be centered in order to support a narrative that at times seems like it’s trying to humiliate Autistic people.

Something I was growing more and more uncomfortable with throughout the season was the focus on Connor’s yawning. “Air hunger” or even anxiety can be a common occurrence with Autistic people, which can lead to contagious yawning (I’m absolutely yawning while writing this). I was grateful that in episode 6, the show highlighted a lovely moment of Connor explaining on his date with Emily how his yawning is a nervous tic. Emily responded with a yawn and agreed that her anxiety can present itself similarly.

The show’s soundtrack has led to polarizing reactions from Autistic viewers on social media.

For some, the songs, which are at times pulled from sources like The Sims 3 soundtrack, feels lighthearted and playful, similar to The Great British Bake Off. Or what other Australian media might use in their shows. This can be compared to American reality dating shows like Love is Blind, which tend to play songs with lyrics that line up with the actions of the scene (no doubt at times annoying for its own reasons).

For others—including a TikTok user who had 21k hearts on their comment at the time of publishing this essay—“The Love on the Spectrum music sounds like the stuff they play in nature documentaries when the bear cubs are tripping up a hill after their mom.” While I can generally get down with a Sims beat, it’s hard to imagine a world where a dating show would play “sweet suspenseful music” over footage of an allistic adult putting on socks and shoes. As a wedding photographer, I’ve taken photos of shoes being put on by marriers hundreds of times during the getting ready process. Perhaps next time I will hum sweet, suspenseful music in my head to see if I’m making a fuss for no reason.

In the video below, Jeremy Andrew Davis highlights how the music accentuates “awkwardness as the defining tone in how the show represents Autistic personalities.”

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Musically framing the series as a documentary, rather than a dating show, leaves some Autistic viewers feeling othered, almost like being on display at a zoo. Whether you like the jaunty music and excessive bird chirping or not, there’s a noticeable pattern in the timing of the entrance of the music. When parents or family members are speaking on their own, there tends to be moments of quiet or dramatic orchestral swells, unless they are recounting a funny anecdote alongside the participant.

In episode 4, David and Abbey are relaxing in outdoor bubble baths during their trip to Africa. Abbey says “David,” and then there’s a long pause. She eventually sighs and shares her desire to get more collectibles. As she asks if he wants more as well, the music picks back up. The music continues to doot-do-doot-do-doot-do-doot while Abbey and David infodump about the types of collectibles they’d like to add to their collections. In the show’s subtitles, sighs are typically denoted to have feelings associated with them (happy, etc.), but when there’s a moment of silence before Abbey speaks, it says [sighs awkwardly].

Pairing the whimsical music with the intros like, “Kate likes beavers. And opening presents. She doesn’t like hot dogs. Or people breaking the rules,” is for sure a stylistic choice that has led to much controversy within the community. While this show is intentionally making different choices from other Netflix dating shows, the contrasting reactions from Autistic and allistic viewers still gives the perception that we’re all rooting for the cast in our own (sometimes flawed) ways.

Reality tv has no shortage of “quirky” neurodivergent dating show contestants. Including Love Is Blind’s Shayne Jansen, who had to disclose his ADHD after being targeted with fueled allegations from fans who insisted he was taking cocaine while on the show. His comments looked more like, “He’s always energetic but seems to be on something? Hope he gets help” and “Watched the whole series 🚩 narcissistic pr#%k.” Jansen explained that being in the pods for hours in front of cameras was uncomfortable, so he relied heavily on caffeine to stay awake, only furthering his anxiety. I’d be curious to see how Jansen would be received from the lens of a neurodivergent-focused reality tv show. Perhaps he too would be given the Buddy the Elf treatment in that multiverse, instead of juggling a barrage of snowflake emojis—a symbol for cocaine—in his comments.

Increasing media depictions of Autistic people is crucial to reducing stigma and stereotypes and increasing representation. However, with any representation, many of us have to brace ourselves from undoubtedly well-meaning, and yet still harmful, allistic responses.

In a TikTok stitch where a viewer captions a video by calling Tanner their spirit animal, Wynter, an AuDHD artist and advocate responds by saying: “I love that Autistic people such as myself can see other Autistic people on screen. But I hate that other people have to watch.”

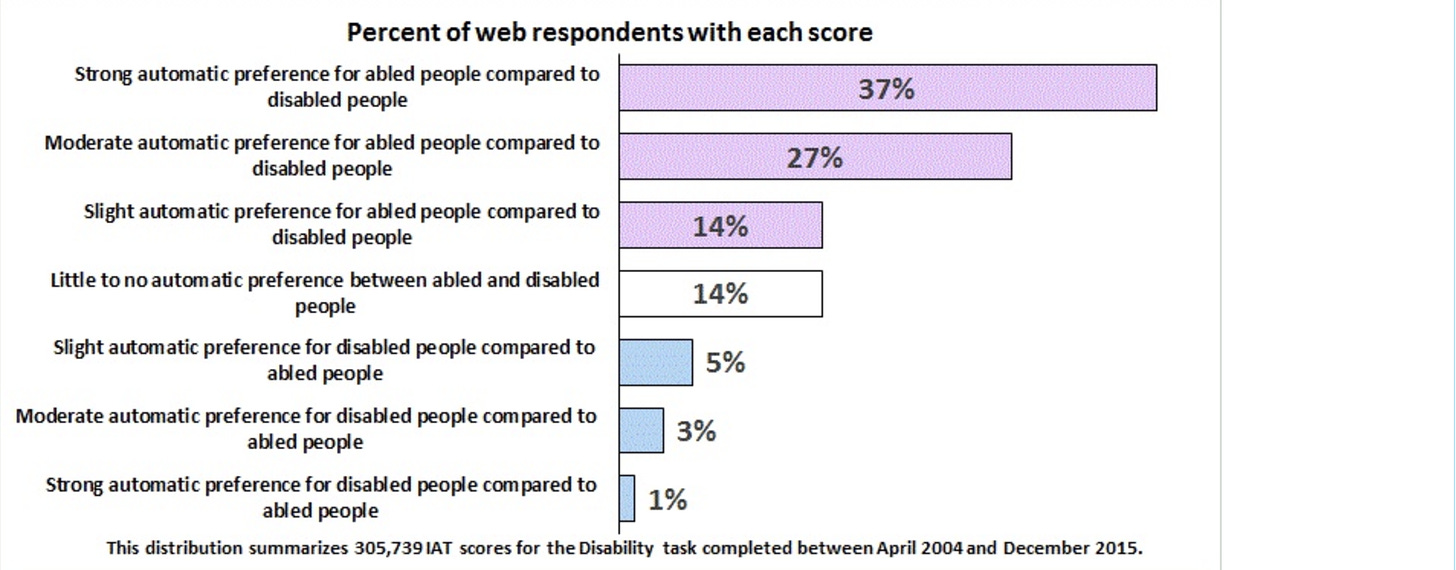

Allistic viewers, if your veiled pity turns into the need to protect us, look no further than within yourself. Consider taking the Harvard’s Implicit Association Test to identify your own biases.

While Love on the Spectrum can’t singlehandedly dismantle allistic people’s internalized ableism and biases, there are still some choices being made that are perhaps worth reinvestigating in future seasons.

Season 1’s Kaelynn recently responded to the Love on the Spectrum critiques by saying in a TikTok caption: “Of course there’s room for improvement…and yes, the community at large SHOULD speak on things that affect them. HOWEVER…when doing so, remember to be inclusive in that dialog. Consider the perspectives of those of us who were actually there. It’s only when we truly come together as a community that we can enact the change we’d like to see. Personally, I think LOTS is a great ✨step✨ toward autism representation in media and there’s plenty of room to grow.”

For me, I know I didn’t marathon the recent episodes for no reason. There is heart to the show, and that heart is the cast of Autistic humans who have taken the time to share their stories with us all. And for that I am grateful.

![A screenshot of Abbey in a bubble bath with the caption [sighs awkwardly] A screenshot of Abbey in a bubble bath with the caption [sighs awkwardly]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F71c2dc55-9026-48b0-9722-51f9d186959f_3783x2166.jpeg)